Smart et al., Appendix 1.

Note: if citing this appendix please use the citation to the original paper

Smart D, Wilmshurst P, Banham N, Turner M, Mitchell SJ. Joint position statement on atrial shunts (persistent (patent) foramen ovale and atrial septal defects) and diving: 2025 update. South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society and the United Kingdom Diving Medical Committee. Diving Hyperb Med. 2025 31 March;55(1):51−55. doi: 10.28920/dhm55.1.51-55. PMID: 40090026.

Bubble contrast echocardiography for divers. Notes regarding quality assurance

Bubble contrast echocardiography relies on the fact that microbubbles reflect ultrasound (i.e., are echogenic) and a right-to-left shunt is revealed by bubbles, appearing as white dots on the echocardiogram screen, in the left heart.

It can be a challenge to perform bubble contrast echocardiography to a high standard, because it requires that a number of actions in quick succession are performed adequately. As with all investigations, quality control is very important to ensure the lowest possible rate of false results.

Some right-to-left shunts are present without provocative manoeuvres.

To achieve a high sensitivity and greater specificity to detect a persistent (patent) foramen ovale (PFO) may require provocative testing to “open” the PFO flap at the same time as bubble contrast is present in the right atrium. This requires a co-operative patient, co-ordination between operator and patient, and precise timing.

PROCEDURE

After obtaining informed consent, that should be suitably documented, insert a venous cannula of at least 20-gauge size. A vein in an antecubital fossa should be used, so that blood can be drawn back into the syringe and so that rapid injection has a short transit time to the heart.

The arm in which the cannula is placed should be elevated to above the height of the heart, so that gravity facilitates rapid passage of the bubble contrast into the right atrium, which ensures better opacification of the chamber with the contrast. The patient is usually in the left lateral position to obtain apical four-chamber images using transthoracic echocardiography. If the cannula is in a right antecubital vein and the arm is rested along the right side of the patient, the cannula will be above the height of the heart. If a left antecubital vein is used, the left arm should be supported above the height of the right atrium.

Injection of bubble contrast into a left arm vein has the advantage that it will detect a right-to-left shunt associated with a left superior vena cava draining to the left atrium, if one is present.

Bubble contrast should be formed by using a three-way tap, attached to the back of the cannula (and not the injection port), with two Luer lock 10 mL syringes. One syringe should contain 7-8 mL of normal saline, 1 mL of air, and 1 to 2 mL of blood withdrawn through the cannula into the syringe. The resulting 10 mL should be forcibly pushed back and forth from one syringe to the other 10-15 times until macroscopic gas is replaced by microbubbles (Figure 1). Before injection, the saline, blood and bubble “contrast” should be moved to one of the syringes, and the syringe should be held with the plunger up, so the last mL containing excess air is not injected. The presence of blood in the contrast seems to stabilise the bubbles, so that they persist as microbubbles for longer in the circulation.

Figure 1

Demonstration of creation of microbubbles in a mix of the patient’s blood and sterile saline

In Figure 1, the intravenous cannula is placed in the left antecubital fossa and secured. The 3-way tap is attached to Luer-lock syringes and the contrast is made by forcing the blood, saline and air mixture between the two syringes. On injection the syringe is held upright so any excess air is not injected.

The initial injection of bubble contrast should be given during normal breathing. The contrast should fill the right atrium and right ventricle, such that the white appearance of the bubbles provides complete opacification, with no “black” (non-echogenic) blood visible between the white bubbles (Figure 2). If there is a large atrial right-to-left shunt and there is complete opacification of the right atrium with bubble contrast, microbubbles may be seen crossing the atrial septum during each normal inspiration. If so, a single injection of bubble contrast may be adequate to confirm that there is an atrial shunt (Figure 2).

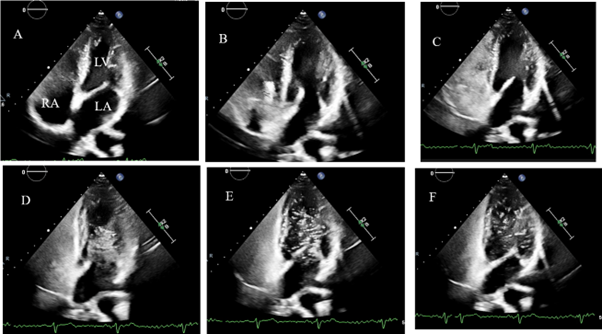

Figure 2

(panels A-F). Apical four chamber images during bubble contrast echocardiography when a patient with a PFO breathed normally. Bubble contrast is bright white and blood is black

In Figure 2, the contrast can be seen entering the right atrium (RA) in panel B and C. By panel D, there is already a bolus of contrast in the left ventricle (LV) spontaneously, indicating a resting right-to-left shunt. The white contrast is densely opacifying the right heart, and is filling the RA along the whole atrial septum. The left atrium (LA) is not very opacified as the bubbles are entering the LV as soon as they cross the septum.

Sometimes an area of bubble-free black is seen adjacent to the atrial septum. This is due to the inflow of blood that does not contain microbubbles from the inferior vena cava: for many patients the Eustachian valve or Chiari network direct the inferior vena cava blood towards the atrial septum, as occurs in foetal life. If there is right-to-left shunting across a PFO, it will not be detected if the blood in the right atrium that is adjacent to the atrial septum is free of bubble contrast. In order to ensure that bubble contrast is adjacent to the atrial septum, provocative manoeuvres may be necessary, and in addition altering the position of the patient by either lying them flatter, or propping them up more, can result in more complete filling of the right atrium with bubble contrast.

PROVOCATION MANOEUVRES AND QUALITY CONTROLS

Even if the initial resting injection shows a right-to-left shunt, further injections are usually necessary to confirm that the shunt size increases with provocative manoeuvres. A bubble contrast injection with a sharp sniff as soon as the right atrium is completely filled with contrast will often open a PFO to reveal a right-to-left shunt, which was not seen during normal breathing, or to increase the amount of shunting. A sniff reduces the intrathoracic pressure suddenly, and the shunt is seen immediately after the sniff. A large number of bubbles entering the left heart following a sniff is diagnostic of an atrial shunt (a PFO or atrial septal defect), rather than a pulmonary shunt. Furthermore, the presence of a shunt with only a sniff indicates that only a small amount of pressure change is required to open a PFO and cause a right-to-left shunt.

Release of a Valsalva manoeuvre is also used to provoke right-to-left atrial shunting (Figure 3). It is important to ensure that there is opacification of the right heart with bubble contrast immediately after the Valsalva release. To ensure that happens the bubble contrast should be injected immediately before the patient starts the Valsalva manoeuvre. To obtain accurate results requires careful performance of the Valsalva release.

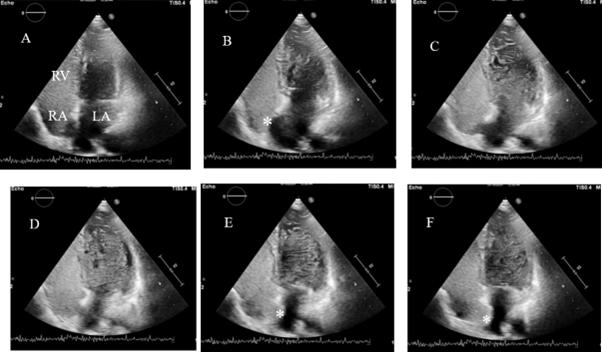

Figure 3

(panels A-F). Bubble contrast echocardiography in the same patient as in Figure 2, showing an increase in the shunt with a Valsalva manoeuvre

Figure 3 shows the same patient during a Valsalva manoeuvre, echo images A-F. The right ventricle (RV) and RA are densely opacified with contrast and in panel B, the atrial septum (*) is bulging towards the RA because at that time the LA pressure is higher than RA pressure at rest. In panels E and F, after release of the Valsalva manoeuvre, the septum (*) is seen to bulge towards the LA, because the LA pressure is lower than the RA pressure. The degree of excursion of the septum indicates the presence of an atrial septal aneurysm or floppy septum that is associated with a larger PFO. In this case the shunt is very large because there is almost completely opacification of the LV with the white bubbles.

The patient is instructed to perform a Valsalva by stopping breathing in a neutral position (so the echocardiographic image is not obscured by the presence of fully inflated lung tissue in the path of the ultrasound beam from the transducer to the patient’s heart), to hold their nose tightly and to close their mouth tightly. The patient is then asked to strain by trying to forcefully exhale, whilst maintaining complete closure of the nose and mouth. It can be helpful to tell the patient to imagine that there is a pressure gauge in the middle of the chest and the pressure should be elevated and maintained at a high level for a period of time, until they are told to release the strain. The patient should maintain the strain until the cardiac chambers appear visibly smaller on the echocardiogram monitor because of the reduction in venous return.

When the cardiac chambers are seen to be smaller the patient is asked to release the Valsalva suddenly, and go back to breathing normally without making large inspiratory or expiratory breaths. At the moment of Valsalva release, one expects to see microbubbles stream rapidly into the right heart, causing complete wall-to-wall opacification of the right heart, and to see the atrial septum bulge across towards the left. At that moment the right atrial pressure has recovered, but the left atrial pressure should still be low. If there is a PFO, a bolus of bubbles would be observed crossing the atrial septum into the left heart at that time, or in one of the next couple of cardiac cycles. If no right-to-left shunt is seen after the first bubble contrast injection with Valsalva release, the procedure should be repeated at least twice more, and possibly up to five times in total, before the test is reported as negative.

Changes during a Valsalva manoeuvre are as follows. At the onset of Valsalva (straining against a closed airway), the intrathoracic pressure is increased and exceeds venous pressure. That causes reduction of venous return to the right atrium. During about 10 seconds, both left and right ventricles can be seen to reduce in size and there is a reduction in the number of bubbles appearing in the right heart. Thus, to quality control the Valsalva manoeuvre, it is important to see reduction in size of both left and right heart chambers, and to see that the flow of bubbles back to the heart decreases.

When the Valsalva is released suddenly, the intrathoracic pressure decreases immediately. This leads to rapid reduction of the pressures in both atria. The right atrium is able to fill rapidly from the venous circulation, which at that time is opacified by bubble contrast. However, the left atrial pressure remains low, because the pressure in the pulmonary veins is also low. Because the right atrial pressure and filling recover more quickly than the left atrial pressure and filling, one often sees the atrial septum bowing towards the left atrium (Figure 4).

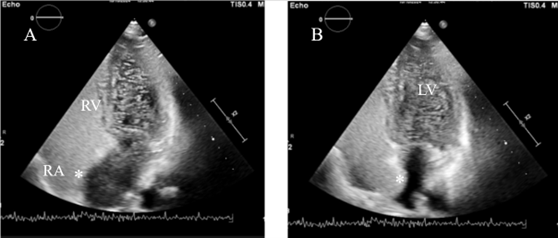

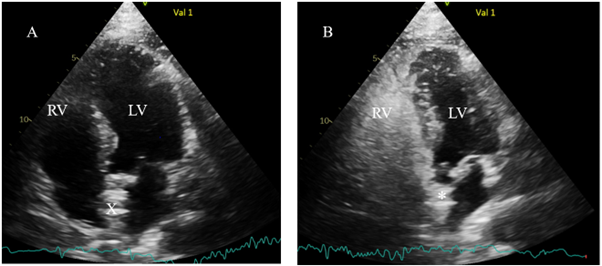

Figure 4

(panels A and B). Larger format image to demonstrate excursion of the atrial septum (*)

In Figure 4 panel A, there is dense and complete opacification of the right heart with contrast with no gaps between bubbles and with the bubbles being right up against the atrial septum (marked as *). In panel B, the atrial septum (*) is bulging towards the left heart and bubble contrast is easily seen in the LV. This shows the quality of bubble contrast and provocative testing that is required, and how a substantial (some call a Grade 4) shunt appears. There is no need to attempt to count the bubbles in the left heart in shunts of this magnitude.

The quality control when the Valsalva manoeuvre is released requires seeing that the right atrium has dramatically filled with dense bubble contrast, but the left heart remains small. If bubble contrast is not present in the right atrium adjacent to the atrial septum, and the septum does not move to the left, the investigation may be inadequate.

Because the haemodynamic changes necessary to open a PFO may vary from patient to patient, it is recommended to make alterations to the duration of the Valsalva manoeuvre, and also consider moving the patient's position, if there is lack of opacification of the right atrium at the time of Valsalva release.

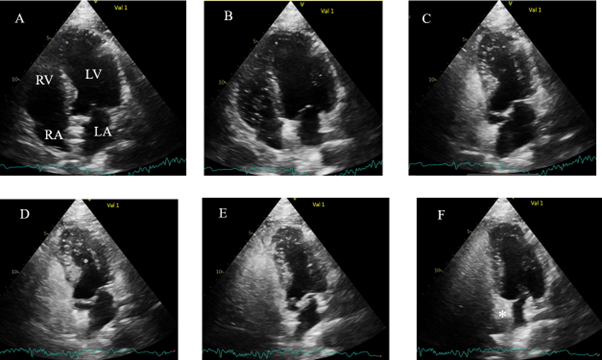

Figure 5

(panels A-F). Apical echocardiogram images before and during a Valsalva manoeuvre

Figures 5 and 6 show an apical echocardiogram view during a Valsalva manoeuvre and immediately after release. In panels A and B, the LV is of normal size. Contrast appears in the RA and RV in panel C. In panels D and E, during the Valsalva manoeuvre, the LV and LA are much smaller because of the reduction in venous return, so the inflow to the heart is reduced. In Panel F the atrial septum (*) is bulging towards the LA because immediately after the release of the Valsalva manoeuvre the RA fills before the LA. An occluder device can be seen in the atrial septum, as this study was performed 6 months following PFO closure.

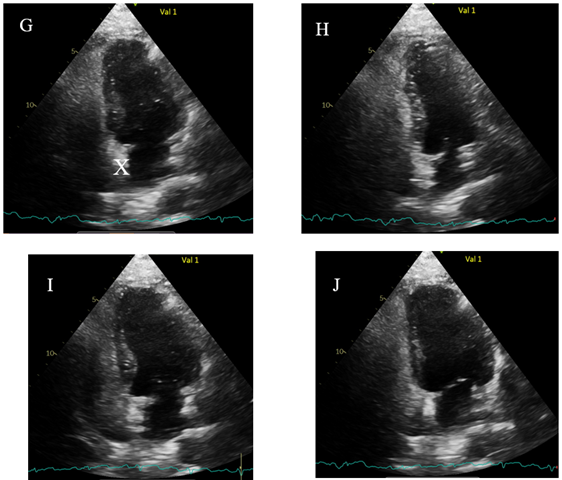

Figure 6

(panels G-J). Apical echocardiogram images with left ventricle returning to normal size after release of the Valsalva manoeuvre

A Gore Cardioform Septal Occluder device (X) can be seen in the atrial septum in panel G, with the device also bulging towards the LA, proving that the RA pressure is greater than the LA. In panels G - J, the LV returns to a normal size. Only occasional bubbles are seen the in the LV representing a tiny residual shunt of no concern. To be certain the Valsalva is effective in reducing venous return, it is important to see the LV reduce in size and to confirm by seeing the bulging of the septum towards the LA.

POTENTIAL FALSE NEGATIVE AND FALSE POSITIVE TESTS

It is essential for quality control that the echocardiogram window provides good images of the heart at the time when one expects bubbles to cross into the left heart. The left heart should be visible and recordable at the time of the sniff and for a few cardiac cycles afterwards. It can be difficult to keep the images of the heart in the image window during Valsalva release when the patient’s intrathoracic pressure changes and the heart changes its position relative to the chest wall (where the ultrasound probe is held), and the patient is likely to move a little. If the echocardiogram image cannot be maintained at the time when a shunt is expected, it can lead to false negative results.

Caution should be exercised when interpreting the appearance of bubbles in the left heart after the provocative manoeuvres, because they may result in a false positive diagnosis of an atrial shunt. When bubbles appear more than 3 cardiac cycles after Valsalva release or a sniff, or if a shunt is present during respiration at rest, the shunt may be trans-pulmonary; either traversing a large arteriovenous malformation or multiple microscopic vascular shunts. If the late shunt appears after Valsalva release, when multiple injections have already been given (and the pulmonary capillaries have trapped many bubbles), a few bubbles can sometimes be seen in the left heart in a patient with normal heart and lungs; this is likely to be a false positive test.

False positive tests can also occur if colloid based contrasts are used. Gelofusine® forms smaller bubbles that will pass through a normal pulmonary circulation.

Figure 7

(panels A and B). Apical echocardiogram images showing occlusion of the PFO

In Figure 7, panel A has no contrast and shows a normal size LV, and the closure device (X) in the atrial septum centrally placed between RA and LA Panel B shows that immediately after Valsalva release, the LV is smaller and the atrial septum (*) is bowing towards the smaller LA. The right heart is full of dense contrast, but the LV has no contrast, showing good occlusion of the PFO.

TO SUMMARISE THE QUALITY CONTROL:

1. An apical view of the heart should be maintained throughout the bubble contrast injection and provocative manoeuvres.

2. In order to ensure rapid arrival of bubbles at the right atrium, bubble contrast should be injected into a vein in an antecubital fossa, with the vein positioned above the level of the right atrium.

3. Bubble contrast should be formed by mixing saline with a small amount of the patient’s blood and a small amount of air.

4. Bubble contrast should completely opacify the right side of the heart so that it appears white. No “black” (non-echogenic) blood should be visible between the bubbles in the right heart.

5. The bubble contrast should be adjacent to the atrial septum at the time of provocative manoeuvres.

6. Valsalva manoeuvres should be quality controlled to ensure that all cardiac chambers reduce in size during the pressurisation of the chest; and on release, the bubble contrast should rush into the right side of the heart and fully opacify the right atrium adjacent to the septum, and the atrial septum should be seen to bulge towards the left atrium, confirming that the right atrial pressure exceeds the left atrial pressure.